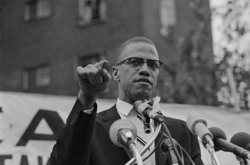

“Who told you to hate the color of your skin?” Malcolm’s words always cut like a knife. That’s because Malcolm X understood that in order to destroy the citadel of white supremacy which rules this country, Black Americans must first destroy the fortresses of anti-Blackness which occupy our own minds.

“Who told you to hate the color of your skin?” Malcolm’s words always cut like a knife. That’s because Malcolm X understood that in order to destroy the citadel of white supremacy which rules this country, Black Americans must first destroy the fortresses of anti-Blackness which occupy our own minds. RNA - I was 12-years-old when I was first introduced, via the Spike Lee film, to the ideas of Malcolm X. It was a shock to the system. Here was someone who did not bother to defend Black people from racist slanders. He never tried to justify why we deserved to be free. Instead, he delivered a scathing indictment of “the White Man,” an indictment of the settler-colonialist US society which had no greatness but that which it stole, Motema Makasi, an activist, wrote in the Workers.Org website.

Growing up with the belief that I must do my best to prove that I was as good as my white peers, to prove that my parents “raised me right,” I never could have conceived of such a line of argument.

Laboring under respectability politics and the burden of representation, I never imagined that it was white “America” who needed to justify their actions to us. But Malcolm said it, and the bell could not be unrung. From that day I on, I could not help but view the world differently.

That was the effect that Malcolm X had on Black Americans — then and now. With no delicacy or trepidation, he snatched away the Black inferiority complex and tossed it in the gutter. In its place, he gave us a worldview that identified — with laser-like precision — the sources of systemic oppression and paired that insight with the courage to call oppression what it is.

Malcolm X did not believe in making apologies for the conditions under which the Black community lived. He spoke often of the effects that drugs and crime had on Black neighborhoods, but he placed them within the proper context of white oppression.

He was never ashamed of the six and a half years he spent in prison. Rather, he used his life experience to demonstrate how African Americans, when separated from their history and culture and placed in an impoverished internal colony, will inevitably suffer from alienation and adopt anti-social tendencies. He asserted the only means of deliverance for Black people was to separate from white supremacy and connect with a sense of pride.

Perspective on self-worth

And therein lies the fundamental difference between Malcolm X, along with the Black Power movement he inspired, and the Black liberal civil rights tradition. It was not Malcolm X’s perspective on violence that set him apart, but his perspective on self-worth.

He was against passively submitting to beatings and attack dogs, not because he believed in violence, but because he believed in himself. He believed that he, along with every other Black person in the US, was a human being with dignity who did not deserve to be degraded by gangs of angry racists.

Self-defense, then, is not an act of resistance against the other, but an affirmation of the self. The preservation of life is the preservation of the dignity and worth of that life. Suffering is only redemptive to those who are in need of redemption, and we who have been tortured by the lash of inequality have no such need.

Che Guevara said that the true revolutionary is guided by love. If that is so, Malcolm X would make us all revolutionaries by teaching us to love ourselves enough to defend ourselves.

That — under the teachings of Malcolm X — is the meaning of self-defense: Not a commitment to radical violence, but a commitment to radical self-lovein the face of overwhelming anti-Black hate.

Liberals will never canonize Malcolm X as a patron saint of “racial progress” or equality. Malcolm X’s message cannot be whitewashed. The white supremacist capitalist state cannot rehabilitate the image of Malcolm X because that image stands in inflexible opposition to racial and class oppression.

Malcolm X never compromised with the oppressor, and so he left nothing behind that could be appropriated and defanged.

To me, Malcolm X is a reminder to never compromise in the face of that oppression. To always see the world as it is, and yet have the courage and the determination to make it how we believe it should be. As he said, to “make it plain.”

Source: workers.org

847/940